Allosaurus

Summary 3

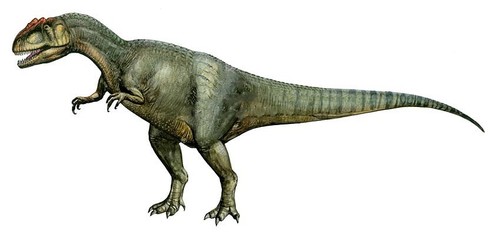

Allosaurus (/ˌæləˈsɔːrəs/[1][2]) is a genus of carnivorous theropod dinosaur that lived 155 to 150 million years ago during the late Jurassic period (Kimmeridgian to early Tithonian[3]). The name "Allosaurus" means "different lizard" alluding to its unique concave vertebrae (at the time of its discovery). It is derived from the Greek ἄλλος/allos ("different, other") and σαῦρος/sauros ("lizard / generic reptile"). The first fossil remains that could definitively be ascribed to this genus were described in 1877 by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh. As one of the first well-known theropod dinosaurs, it has long attracted attention outside of paleontological circles. Indeed, it has been a top feature in several films and documentaries about prehistoric life.

Allosaurus was a large bipedal predator. Its skull was large and equipped with dozens of sharp, serrated teeth. It averaged 9.5 metres (31 ft) in length, though fragmentary remains suggest it could have reached over 12 m (39 ft). Relative to the large and powerful hindlimbs, its three-fingered forelimbs were small, and the body was balanced by a long and heavily muscled tail. It is classified as an allosaurid, a type of carnosaurian theropod dinosaur. The genus has a complicated taxonomy, and includes an uncertain number of valid species, the best known of which is A. fragilis. The bulk of Allosaurus remains have come from North America's Morrison Formation, with material also known from Portugal and possibly Tanzania. It was known for over half of the 20th century as Antrodemus, but a study of the copious remains from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry brought the name "Allosaurus" back to prominence and established it as one of the best-known dinosaurs.

As the most abundant large predator in the Morrison Formation, Allosaurus was at the top of the food chain, probably preying on contemporaneous large herbivorous dinosaurs, and perhaps even other predators. Potential prey included ornithopods, stegosaurids, and sauropods. Some paleontologists interpret Allosaurus as having had cooperative social behavior, and hunting in packs, while others believe individuals may have been aggressive toward each other, and that congregations of this genus are the result of lone individuals feeding on the same carcasses.

Allosaurus was a typical large theropod, having a massive skull on a short neck, a long, slightly sloping tail and reduced forelimbs. Allosaurus fragilis, the best-known species, had an average length of 8.5 m (28 ft),[4] with the largest definitive Allosaurus specimen (AMNH 680) estimated at 9.7 meters (32 feet) long,[5] and an estimated weight of 2.3 metric tons (2.5 short tons).[5] In his 1976 monograph on Allosaurus, James H. Madsen mentioned a range of bone sizes which he interpreted to show a maximum length of 12 to 13 m (39 to 43 ft).[6] As with dinosaurs in general, weight estimates are debatable, and since 1980 have ranged between 1,500 kilograms (3,300 pounds), 1,000 to 4,000 kg (2,200 to 8,800 lb), and 1,010 kilograms (2,230 pounds) for modal adult weight (not maximum).[7] John Foster, a specialist on the Morrison Formation, suggests that 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) is reasonable for large adults of A. fragilis, but that 700 kg (1,500 lb) is a closer estimate for individuals represented by the average-sized thigh bones he has measured.[8] Using the subadult specimen nicknamed "Big Al", researchers using computer modelling arrived at a best estimate of 1,500 kilograms (3,300 lb) for the individual, but by varying parameters they found a range from approximately 1,400 kilograms (3,100 lb) to approximately 2,000 kilograms (4,400 lb).[9]

Several gigantic specimens have been attributed to Allosaurus, but may in fact belong to other genera. The closely related genus Saurophaganax (OMNH 1708) reached perhaps 10.9 m (36 ft) in length,[5] and its single species has sometimes been included in the genus Allosaurus as Allosaurus maximus, though recent studies support it as a separate genus.[10] Another potential specimen of Allosaurus, once assigned to the genus Epanterias (AMNH 5767), may have measured 12.1 meters (40 feet) in length.[5] A more recent discovery is a partial skeleton from the Peterson Quarry in Morrison rocks of New Mexico; this large allosaurid may be another individual of Saurophaganax.[11]

David K. Smith, examining Allosaurus fossils by quarry, found that the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry (Utah) specimens are generally smaller than those from Como Bluff (Wyoming) or Brigham Young University's Dry Mesa Quarry (Colorado), but the shapes of the bones themselves did not vary between the sites.[12] A later study by Smith incorporating Garden Park (Colorado) and Dinosaur National Monument (Utah) specimens found no justification for multiple species based on skeletal variation; skull variation was most common and was gradational, suggesting individual variation was responsible.[13] Further work on size-related variation again found no consistent differences, although the Dry Mesa material tended to clump together on the basis of the astragalus, an ankle bone.[14] Kenneth Carpenter, using skull elements from the Cleveland-Lloyd site, found wide variation between individuals, calling into question previous species-level distinctions based on such features as the shape of the horns, and the proposed differentiation of "A. jimmadseni" based on the shape of the jugal.[15]

The skull and teeth of Allosaurus were modestly proportioned for a theropod of its size. Paleontologist Gregory S. Paul gives a length of 845 mm (33.3 in) for a skull belonging to an individual he estimates at 7.9 m (26 ft) long.[16] Each premaxilla (the bones that formed the tip of the snout), held five teeth with D-shaped cross-sections, and each maxilla (the main tooth-bearing bones in the upper jaw) had between 14 and 17 teeth; the number of teeth does not exactly correspond to the size of the bone. Each dentary (the tooth-bearing bone of the lower jaw) had between 14 and 17 teeth, with an average count of 16. The teeth became shorter, narrower, and more curved toward the back of the skull. All of the teeth had saw-like edges. They were shed easily, and were replaced continually, making them common fossils.[6]

The skull had a pair of horns above and in front of the eyes. These horns were composed of extensions of the lacrimal bones,[6] and varied in shape and size. There were also lower paired ridges running along the top edges of the nasal bones that led into the horns.[6] The horns were probably covered in a keratin sheath and may have had a variety of functions, including acting as sunshades for the eye,[6] being used for display, and being used in combat against other members of the same species[16]17.[6] There was a ridge along the back of the skull roof for muscle attachment, as is also seen in tyrannosaurids.[16]

Inside the lacrimal bones were depressions that may have held glands, such as salt glands.[18] Within the maxillae were sinuses that were better developed than those of more basal theropods such as Ceratosaurus and Marshosaurus; they may have been related to the sense of smell, perhaps holding something like Jacobson's organ. The roof of the braincase was thin, perhaps to improve thermoregulation for the brain.[6] The skull and lower jaws had joints that permitted motion within these units. In the lower jaws, the bones of the front and back halves loosely articulated, permitting the jaws to bow outward and increasing the animal's gape.[19] The braincase and frontals may also have had a joint.[6]

Allosaurus had nine vertebrae in the neck, 14 in the back, and five in the sacrum supporting the hips.[20] The number of tail vertebrae is unknown and varied with individual size; James Madsen estimated about 50,[6] while Gregory S. Paul considered that to be too many and suggested 45 or less.[16] There were hollow spaces in the neck and anterior back vertebrae.[6] Such spaces, which are also found in modern theropods (that is, the birds), are interpreted as having held air sacs used in respiration.[21] The rib cage was broad, giving it a barrel chest, especially in comparison to less derived theropods like Ceratosaurus.[22] Allosaurus had gastralia (belly ribs), but these are not common findings,[6] and they may have ossified poorly.[16] In one published case, the gastralia show evidence of injury during life.[23] A furcula (wishbone) was also present, but has only been recognized since 1996; in some cases furculae were confused with gastralia.[23][24] The ilium, the main hip bone, was massive, and the pubic bone had a prominent foot that may have been used for both muscle attachment and as a prop for resting the body on the ground. Madsen noted that in about half of the individuals from the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, independent of size, the pubes had not fused to each other at their foot ends. He suggested that this was a sexual characteristic, with females lacking fused bones to make egg-laying easier.[6] This proposal has not attracted further attention, however.

The forelimbs of Allosaurus were short in comparison to the hindlimbs (only about 35% the length of the hindlimbs in adults)[25] and had three fingers per hand, tipped with large, strongly curved and pointed claws.[6] The arms were powerful,[16] and the forearm was somewhat shorter than the upper arm (1:1.2 ulna/humerus ratio).[26] The wrist had a version of the semilunate carpal[27] also found in more derived theropods like maniraptorans. Of the three fingers, the innermost (or thumb) was the largest,[16] and diverged from the others.[26] The phalangeal formula is 2-3-4-0-0, meaning that the innermost finger (phalange) has two bones, the next has three, and the third finger has four.[28] The legs were not as long or suited for speed as those of tyrannosaurids, and the claws of the toes were less developed and more hoof-like than those of earlier theropods.[16] Each foot had three weight-bearing toes and an inner dewclaw, which Madsen suggested could have been used for grasping in juveniles.[6] There was also what is interpreted as the splint-like remnant of a fifth (outermost) metatarsal, perhaps used as a lever between the Achilles tendon and foot.[29]

Fontes e Créditos

- (c) Geoffrey Lowe, alguns direitos reservados (CC BY-SA), https://www.flickr.com/photos/geoff-lowe/7286535322/

- (c) calgaryzoo, todos os direitos reservados

- Adaptado por calgaryzoo de uma obra de (c) Wikipedia, alguns direitos reservados (CC BY-SA), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allosaurus